HIPAA Needs a Revamp

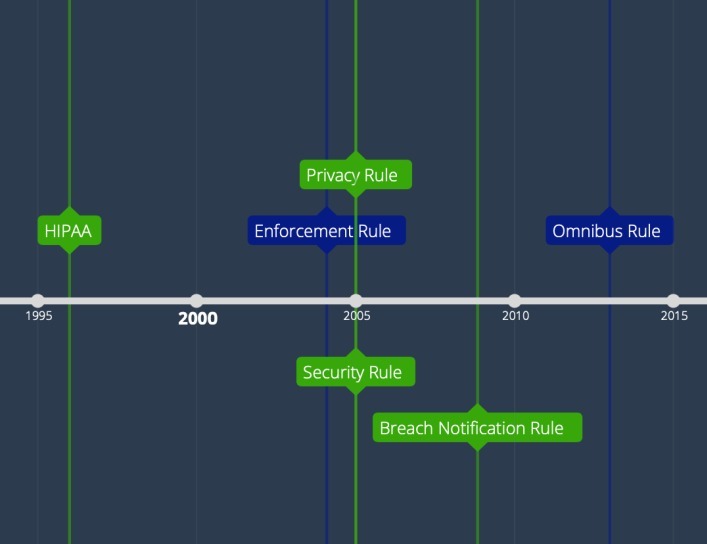

a timeline of the original HIPAA rules (green) and additional legislation (blue)

Mental Health apps are slipping through the cracks of data privacy laws’ archaic policies — exposing the loose regulation within tech and the ever-static scope of HIPAA.

Over a third of Americans live in areas that lack mental health professionals. With the inaccessibility of mental healthcare, a few other options arise. Mental health apps like BetterHelp allow you to access therapy through a few clicks of a button and the price of $380 a month. As the faint line between customer and patient continues to blur in the healthcare sphere, data experts and politicians are wondering to what extent mental health apps collect and share personal data with third-party apps Facebook and Google.

There are no guidelines for data security in health apps according to Uprise Health. A study by the US Department of Health and Human Services found ‘large gaps in policies around access, security, and privacy’. Laws and regulations have failed to keep pace with the constant innovation.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 protects patients’ health information given to health professionals like therapists. The law’s purpose is to guard individuals’ protected health information, or PHI, but it has failed to keep up with the advancement of technology. The pre-smartphone law has had few major changes since its previous enactment. The last major update to HIPAA took effect in 2013.

BetterHelp and Talkspace claim to be covered entities. Mental health apps tend to fall in the gray area, but users may be under the impression that their information is as safe as it would be with any therapist or healthcare provider. A study in 2019 found that out of 36 top-ranked apps for depression and smoking cessation ‘29 transmitted data to services provided by Facebook or Google, but only 12 accurately disclosed this in a privacy policy.’

With long lines for therapy and waitlists increasing in size, mental health apps like BetterHelp may seem like a plausible option. After all, anyone with a smartphone or other device can access the apps. The intake process for BetterHelp includes a more than 40-question questionnaire to match users with a therapist right for them. Some of the information collected includes your age, gender identity, sexual orientation and reasons for using the app. Included in the account package is a weekly live session via video, phone, or chat. With the package, help is accessible from your palm as users can message their therapist anytime, from anywhere.

The American Psychiatric Association created an app evaluation model for mental health apps which uses multiple factors, including data privacy, in its analysis. Using the model, psychiatrists found that BetterHelp also collects conversations between therapists and users. According to BetterHelp, users can anonymize their data, shred text conversations, and request data deletion under applicable law’, but none of these processes are explicitly stated in their privacy policy. Some of the app’s reasonings for the collection of data, similar to that of other mental health apps, better the quality of services provided and personalize the user experience.

“What they do, at least for BetterHelp and for most apps […] is send data to Facebook so that they can then retarget advertisements to people who have visited those apps,” investigative reporter, Dhruv Mehrota explained. “So if you download Betterhelp and or ZocDoc for a while, a bunch of data gets sent to Facebook. Then two days later when you’re browsing through Instagram, and you might get an ad for BetterHelp or for, you know, ZocDoc.”

All of this information is disseminated using pixels. Facebook developers describe Meta Pixel as a piece of code companies can add to their websites. It tracks numerous types of data. Notably, the tracking tool can collect button-click data which includes information regarding ‘any buttons clicked by site visitors, the labels of those buttons and any pages visited as a result of the button clicks.’

Facebook is no stranger to the medical field. Just months ago it was revealed that the company was receiving sensitive medical information from hospital websites that used the Big-tech company’s Pixel code. Researchers for The Markup found that out of the top 100 best hospitals in the world, 33 had websites that used the code that had been collecting sensitive patient health information.

“It allows Facebook to target advertisements at people based on like their mental health or based or protected categories or things that you don’t like, things that are like privacy, invasive and sensitive. It allows them to target those people with ads. And sometimes those ads can be malicious, ” Mehrota, said.

Senators Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, and Ron Wyden sent a letter to Alon Mata, founder and president of BetterHelp, and Douglas Braunstein, chairman and interim chief executive officer of TalkSpace. The letter questioned the extent to which the apps collect and share personal data. Senator Booker’s and Senator Wyden’s press teams were contacted for a statement but failed to comment.

Regarding the scope of the law, the HHS wrote that ‘a growing number of organizations that maintain, transmit, or receive health information about individuals fall outside the scope of HIPAA’. But because numerous health data privacy bills have been cut up, glued back together, and sniped by Congress, little progress has been made to fill the cracks of data privacy laws.

Post a comment